In November of 1956, singer/pianist Nat “King” Cole became the first Black man to host a variety show on network television. Though he eventually had multiple Billboard hits including Mona Lisa, L-O-V-E, and Nature Boy, he never secured a National sponsor for this groundbreaking program. Major markets, especially those in the South, pressured advertisers to drop their support of the broadcast. Despite an array of popular guest stars with household names, beaten down by the color barrier, NBC and Cole agreed to terminate the venture the following year after 53 episodes.

Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole, written by Colman Domingo and Patricia McGregor, uses the final taping of the Nat “King” Cole Show to explore not only this chapter in the life of the beloved crooner, but the systematic erasure of Black voices. It’s an intriguing pick for a central character. Though Cole participated in civil rights marches and avoided segregated venues, he felt his public role was one of an entertainer. He sang ballads, not protest songs, even after a cross had been burned on the lawn of his home in a wealthy white Los Angeles neighborhood.

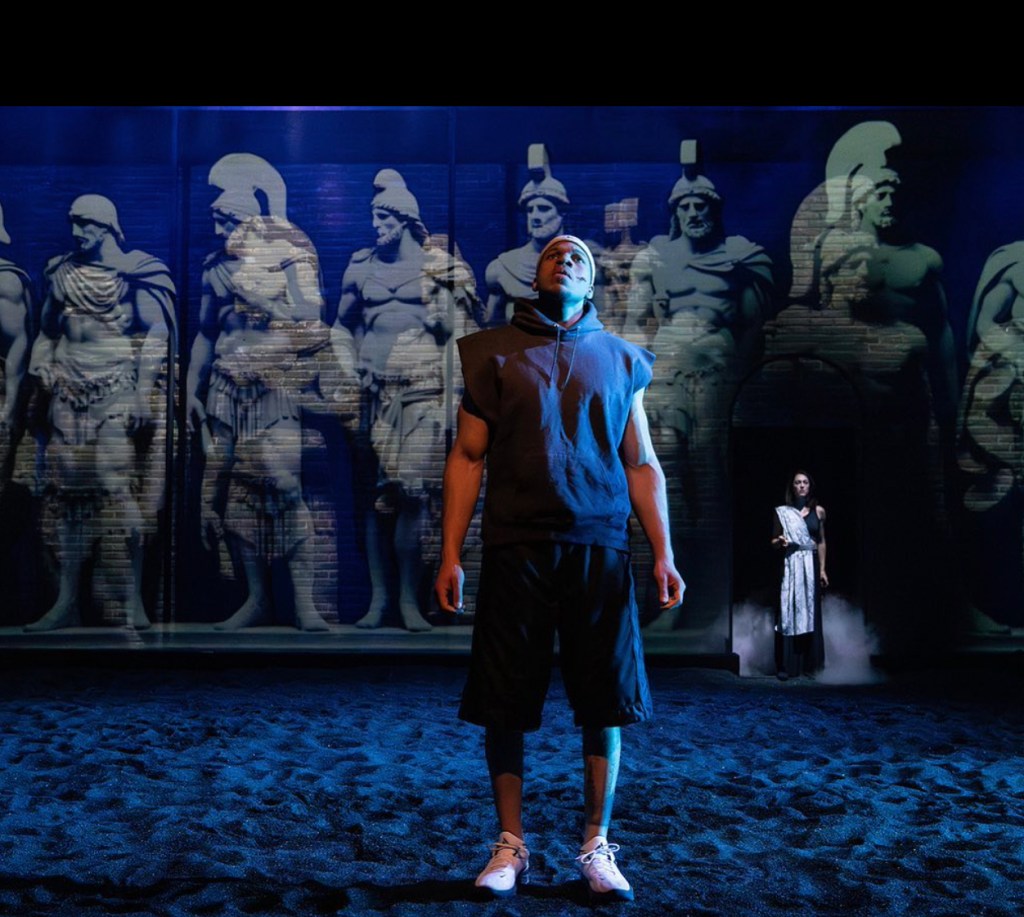

The play is set in a television studio (scenic design by Clint Ramos) complete with an applause sign, clever lighting (Stacey Derosier), and a live “Nelson Riddle” band on the stage. This enables the easy integration of music, live-feed camera work and audience reaction. However, it quickly becomes obvious that this is not a recreation of one night. Shortly before airtime someone (someTHING) causes the ghost light to flicker and briefly go out, allowing the spirit of Sammy Davis Jr. to explode onto the scene. In an effort to inspire Cole to go out on a combative note, The Rat Packer takes him through a phantom version of events. Classic song lyrics are incorporated into the spoken dialogue along with a mix of historical fact as seen through the lens of modern times and Cole’s personal reflection as imagined by Domingo and McGregor.

Dulé Hill gives soothing voice and gravitas to Cole, a part he cultivated at the Peoples’ Light in Malvern, PA and further developed at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles. Daniel J. Watts, also reprising his role, grabs Davis by the lapels, practically ricocheting off the walls with intensity. He is high octane gasoline to Hill’s humming battery pack. Playwright McGregor directs, bouncing the two very different friends off one another, culminating in a dynamic dance number (choreography by Edgar Godineaux with tap by Jared Grimes). Though the plot line is choppy and likely to challenge those unfamiliar with the named celebrities and cultural touchstones, the songbook alone (arrangements and orchestrations by John McDaniel) makes for highly satisfying entertainment.

Hill and Watts positively dazzle in the leads, capturing key qualities of their characters and steering clear of imitation. The action is kicked off by Elliott Mattox’s convivial Stage Manager. Cole’s white producer is portrayed in myriad forms by Christopher Ryan Grant. Krystal Joy Brown makes an early impression as a purring Eartha Kitt, later embodying an enchanting daughter Natalie Cole. Also displaying range is another vet of the previous run, Ruby Lewis, who depicts both spunky Betty Hutton and sultry Peggy Lee. Matriarch Perlina Coles, who first introduced Cole to the piano, is played with soulful sincerity by Kenita Miller with Mekhi Richardson performing as young Nat (and a younger Billy Preston) the afternoon I attended. Adding a comedic touch is Kathy Fitzgerald as make-up artist Candy. She is also featured in the highly creative live commercials that run throughout the program.

You feel the ripples of connection move through different sectors of the audience depending on whether it is Cole performing his rendition of The Christmas Song, Lift Every Voice and Sing vocalized by mother Perlina, or young Natalie joining him for a duet of Unforgettable (something she created in the studio long after his death). When you layer in the profound racism, disgraceful accepted stereotypes, and aggressions micro and macro, the entire experience becomes a social study as well as a piece of engaging theater.

Likely to fill you with a bubbling combination of elation and frustration, Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole provides a worthwhile conclusion to a bold season at New York Theatre Workshop. Performances continue through June 29 on the main stage at 79 East 4th Street. Runtime is 90 minutes without intermission. The actors smoke heavily, making me grateful to remain a mask-wearer. Tickets start at $49 and are available at https://www.nytw.org/show/lights-out-nat-king-cole/.