In 2011, a number of Egyptian youth groups gathered together in Tahrir (Liberation) Square to protest the corrupt authoritarian rule of President Hosni Mubarak. His 30 year stranglehold on power had led to economic stagnation, human rights violations, and media restrictions. The young peoples’ acts of civil disobedience in concert with a series of labor strikes forced Mubarak’s resignation and brought about a democratic election. Their victory was short lived, however, and Egypt now stands at a miserable 18 out of 100 on the Freedom House scale.

Inspired by a photo of several of the activist artists, brothers Daniel and Patrick Lazour wrote We Live in Cairo, developing the score and book over ten years. The results are inconsistent in their ability to sway the audience, primarily carried along on waves of tuneful music. Most numbers combine instruments and musical themes from Egypt with traditional structures including love ballads and rock anthems. Director Taibi Magar joined the collaboration to add depth and movement to song. The voices of the all-Arab ensemble blend beautifully (vocal arrangements by Madeline Benson) even when their characters falter. For the scene depicting the toughest days of uprising, the musicians join the actors center stage, enveloping them with melody.

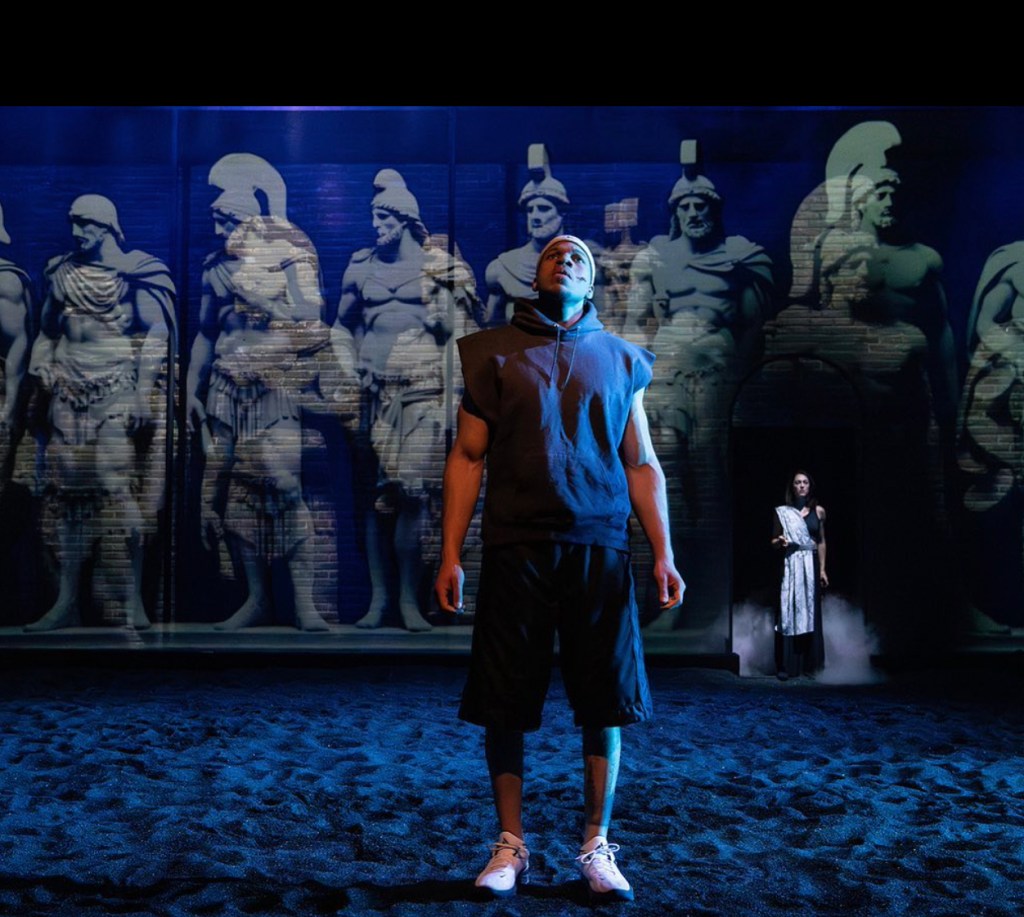

The atmosphere developed by the design team wraps the audience in the sights and sounds of the struggle for freedom. Tilly Grimes’ set is kept simple with a collection of pillows, rugs, lamps and household items filling a few shelves. The visual emphasis is on the evocative projections designed by David Bengali, some of which appear overhead. He and lighting designer Bradley King added their graphical layers to the look and feel when they joined the crew during the run at A.R.T. in Boston.

Unfortunately, the story, though it was restructured several times, lacks the same level of vibrancy. While the idea of looking at this revolution through varying lenses of artistry, policy, and simple human compassion is an interesting concept, the issues are all frustratingly abbreviated and the actions poorly motivated. Initially apolitical and fearful, Layla (Nadina Hassan) suddenly turns her entire life inside out based on exposure to a single image. The societal significance of her boyfriend, Amir (Ali Louis Bourzgui), and his brother Hany (Michael Khalid Karadsheh) living as Coptic Christians in the majority Muslim country is mentioned, but never meaningfully explored. Fadwa (Rotana Tarabzouni) is so driven by her identity as the child of dissidents that her every opinion becomes a cause which muddies their significance. The attraction between the majestic Karim (John El-Jor) and the tentative Hassan (Drew Elhamalawy) is covered over as quickly as one of Karim’s satiric murals. The vagaries of this critical thread border on homophobic. Even the impact from country’s former status as a British colony doesn’t receive more than a single line.

New York Theater Workshop, which has been helping to nourish this production for nearly 7 of the 10 development years, has done what they can to broaden the world of the play beyond the walls of the theater. E-tickets include the promotion of local Egyptian restaurants, invitations to post-show topical talkbacks at their sister space, and lighter cultural fare like a hummus-making contest. A brief historical timeline and the “origin story” of the production are inserted into the program.

Like the ending of the Arab Spring it depicts, We Live in Cairo ultimately fizzles. But it leaves behind a feeling of purpose that makes the experience worthwhile at this delicate point in our own history. The Off-Broadway premiere continues through November 24 at New York Theatre Workshop, 79 East 4th Street in Manhattan. The performance runs 2 ½ hours with one intermission and contains images and sounds of a violent nature. Tickets begin at $49 and can be purchased at https://www.nytw.org/show/we-live-in-cairo/tickets/ or by calling the NYTW box office at 212-460-5475. You will get a better sense of place seated further back from the stage. This is the first play of four in the NYTW 2024-25 season and subscriptions are still available for as little as $230.

Blue Ridge

Alison only knows one way of being. All waving arms and defensive language, she’s a fast talker in all the meanings of that phrase. Having been incarcerated for taking a hatchet to her lover’s car, she’s been released into the loving care of a church-sponsored sober house in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina. We meet her at her very first group session where she recites Carrie Underwood lyrics instead of the bible passage she’s supposed to have prepared. Within minutes she’s telling the circle why she’s not really responsible for her crime and emphasizing that, having never done drugs, she doesn’t have need of any one of the twelve steps.

Anyone who has experience with someone in recovery will know exactly how this story is going to unfold. That’s the essential problem with Blue Ridge, now playing at the Atlantic Theater Company’s Linda Gross Theater. While Abby Rosebrock’s script is beautifully written with textured dialogue, it doesn’t have anything new to say about mental health, boundary issues, or the powers of addiction in its many forms. Only those who find a new path have a real prayer of moving on intact enough to survive in the outside world.

From lower left: Peter Mark Kendall, Chris Stack, Kyle Beltran, Kristolyn Lloyd, Nicole Lewis and Marin Ireland in Blue Ridge. Photo by Ahron R. Foster.

In the hands and body of stage steady Marin Ireland, Alison is particularly irksome. Her constant shrillness and twitching makes it hard to believe anyone in this substitute family would warm to her. This is especially true of her devoted roommate Cherie, played with deep sincerity by the excellent Kristolyn Lloyd. The male housemates’ reactions come from two diametrically opposed yet equally predictable directions. Peter Mark Kendall brings genuine vulnerability to the easily beguiled Cole while the endlessly watchable Kyle Beltran’s Wade creates friction in his struggle to find inner strength. The program’s co-founders are equally ill-equipped to lead everyone safely through a troubled journey. Pastor Hern (a smooth Chris Stack) weakly attempts to guide the housemates in a more mindful direction, and Nicole Lewis’s insufficiently defined Grace generally lives up to her name by simply finding the good in what comes naturally to each of her residents.

Director Taibi Magar successfully explores the shifting mood as the house moves from warm community to too close for comfort. Confrontations have a palpable and fiery emotional core. Her pacing is off, though, with the play running nearly 15 minutes over the prescribed two hours on Thursday night. Mikaal Sulaiman provides the intelligently curated soundtrack for both conflict and healing. Unfortunately, some of the other design choices are distracting. Why is the ten year old furniture of Adam Rigg’s set in a palate associated with the late 70s? Why does Amith Chandrashaker’s lighting incorporate an incongruous brilliant December sunshine streaming through the window and ugly fluorescent overheads that play a supporting role for just a few minutes? Why, while indicating the passage of time through Thanksgiving throws and a Rudolf mantlepiece, do we need to break the story’s flow and see each item put in place by the glow of a proscenium of LEDs?

Taken as a whole, this production of Blue Ridge is flawed and consequently frustrating. Writer Rosebrock has obvious talent, but her storytelling has not yet been brought into focus. However, if you are fascinated by the ways in which broken people can either fit together with or puncture those around them, you may find enough with which to engage. This limited run is scheduled through Sunday, January 27th. Regular tickets begin at $65 and can be purchased online at atlantictheater.org, by calling OvationTix at 866-811-4111, or in person at the Linda Gross Theater box office (336 West 20th Street between 8th and 9th Avenues).